Today, I am reading: The world is chasing methane

Despite our obsession with carbon dioxide, methane could be a handier/ˈhændi/handy ally/ˈælaɪ/ to fight climate change

What do a rice field, a cow, a bog, and a coal mine have in common? Well, there might be more than one answer, but one thing is certain: all of them are “gassy”. They all release methane, a gas not as famous as carbon dioxide, yet infamous for its capacity to trap heat. And as its emissions are on the rise, the world is paying more attention to it. Scientists and governments see in methane a way to achieve faster results on climate mitigation. But to tackle methane means knowing exactly how much of it gets into the atmosphere and who’s to blame.

Methane comes from quite a few natural and human-related sources. About a third of its global emissions originate in wetlands, where massive amounts of organic matter produce methane when decomposing/ˌdiːkəmˈpəʊz/. Agriculture is the biggest contributor of human-induced methane, bringing in more than a quarter of anthropogenic emissions, primarily from livestock and crops grown in flooded/flʌd/ paddies/ˈpædi/paddy. Methane is a by-product of manure/məˈnjʊə(r)/ pits and ruminants’/ˈruːmɪnənt/ burping/bɜːp/burp, while in fields, such as rice, bacteria that decompose underwater create methane. Another quarter of the worldwide methane emissions comes from the oil and gas industry, which causes frequent gas leaks/liːk/ and releases methane. Other sources include biomass burning and thawing/θɔː/thaw permafrost/ˈpɜːməfrɒst/.

But what makes methane the second largest contributor to climate change is its power to heat the atmosphere – being about 20 times as potent/ˈpəʊtnt/ per unit as carbon dioxide. This means that releasing 1kg of methane is like emitting 84kg of carbon dioxide. And as global methane emissions are rapidly increasing, we should expect more intense/ɪnˈtens/ warming.

In 2020, methane reached its highest concentrations/ˌkɒnsnˈtreɪʃn/ since satellite/ˈsætəlaɪt/ records began in 2003, according to preliminary data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). The Global Carbon Project indicates a 9 per cent increase in 2017 compared to 2000-2006 and points to agriculture and waste management as two likely drivers of the rise. “Over the past decade, people realised methane was going up really fast – and this is very problematic,” says Dr. Drew Shindell, a climate scientist at Duke University and lead author of the UN’s 2021 Global Methane Report.

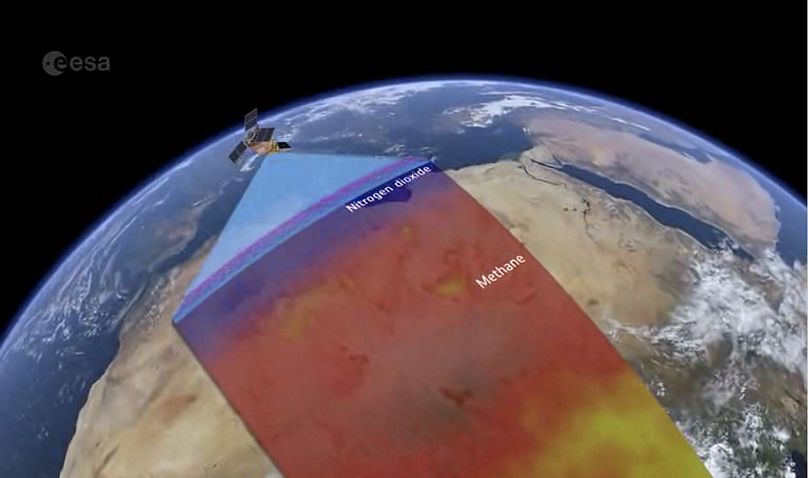

But the culprits/ˈkʌlprɪt/ are still under debate. “Surely, there is a strong human influence in this growth,” says Dr. Ilse Aben, a senior scientist at the SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research and co-principal investigator for the TROPOMI instrument, which makes observations of methane onboard the Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite. “But distinguishing/dɪˈstɪŋɡwɪʃ/ natural from anthropogenic emissions is always complicated.”

While carbon dioxide remains in the air for 300 years, making it a matter of urgency/ˈɜːdʒənsi/ to reduce its emissions, methane stays there only a little over a decade. So slashing /slæʃ/methane emissions could provide quick benefits for climate mitigation. “What we found is that controlling methane is attractive and beneficial,” says Dr. Shindell about the UN report. “For example, if action to reduce methane is taken this year, we would see the concentrations changing already in the year after.” And as methane contributes to pollution – when it mixes with combustion/kəmˈbʌstʃən/ exhausts in the lower atmosphere, it reacts to create ozone which harms our respiratory/rəˈspɪrətri/ system – this reduction could bring immediate health advantages for people.

Climate, however, can take about a decade or more to benefit. “But that is still very fast compared to almost anything else you could do to mitigate climate change,” says Dr. Shindell. For example, cutting methane exhausts from oil and gas by 45 per cent in the next four years, which equals closing 1,300 coal-fired power plants, would benefit the climate in the next 20 years. At a larger scale, halving human-related methane globally by 2050 could reduce warming by 0.2°C in the next 30 years, says the European Commission. “People so far haven’t put that picture together – but as benefits are so obvious, it shouldn’t be that difficult to get people on board,” says Dr. Shindell.

Refined /rɪˈfaɪn/observations bring the goal closer

Momentum/məˈmentəm/ for methane mitigation is growing. The European Union’s strategy on methane wants to boost/buːst/ ambition on reducing the emissions of the EU’s dominant non-CO2 greenhouse gas by 35-37 per cent until 2030 (compared to 2005 levels). To do so, it seeks to improve monitoring and reporting of methane emissions principally/ˈprɪnsəpli/ via/ˈvaɪə/ its Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS). Earlier this year, the US State Department also announced it would invest $35 million into REMEDY, a programme that will develop technologies to reduce methane emissions in the oil, gas, and coal/kəʊl/ industries. Globally, 45 countries producing about three-quarters of the world’s methane emissions are part of the Global Methane Initiative, which also focuses on methane mitigation in these industries.

But to reduce methane at the source requires precise monitoring. SRON uses many measurements in-situ across the world, where people take samples of air for analysis explains Dr. Aben. “That network of about 80 stations is quite good for following how methane is roughly changing globally. But it’s not enough to give us information where the sources of methane are.”

Unlike carbon dioxide, methane emissions are more elusive/ɪˈluːsɪv/, explains Dr. Sergio Noce, a researcher at the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change and contributor to the Global Carbon Project. “The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change tells us that uncertainty about CO2 emissions is lower than that of methane, probably because we know more about where CO2 is produced, and the observation network is much more developed. For methane, there is no globally accurate /ˈækjərət/data on production activities, and sampling is not equally distributed […]. We know a lot about some countries and very little or nothing about others.”

“You really need global coverage, and that’s where satellite observations come in,” says Dr. Aben. “Measurements are challenging – once emitted, methane blends/blend/ into the air and travels. So, in a location, you only see an average methane concentration, but the methane you measure might also come from elsewhere. We look at variations/ˌveəriˈeɪʃn/ of these concentrations across the world and try to pinpoint and estimate the emissions.” But the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) can provide a much finer view of emissions, collecting data off small areas of 5 by 7.5km and providing as much as 40 million observations daily. “For the first time, we have full global coverage and high-resolution observations,” says Dr. Aben.

Possibly the most important data needed for mitigation is knowing who the biggest emitters of methane, or super-emitters, are. As natural sources also put significant amounts of methane in the atmosphere, telling what is human-induced and what is natural is still difficult. “In some cases, you might have oil and gas facilities close to wetlands, so it is complicated to tell exactly how much methane is coming from where,” Dr. Aben explains. So determining the super emitters helps.

TROPOMI looks exactly for those super-emitters – point sources such as coal mines or leaks from oil and gas extraction. “We try to focus on the ones that really pop out and analyse that in more detail. We go for the low-hanging fruit,” says Dr. Aben. “We collaborate /kəˈlæbəreɪt/with other partners with smaller satellites who can measure methane at very fine scales.” After TROPOMI detects emissions at global levels, it provides the locations that stand out, and smaller satellites can zoom in on smaller areas to tell which infrastructure is responsible.

Kayross, a European technology start-up, uses data from Copernicus Sentinel-5P, as well as in-situ data and artificial intelligence to monitor methane globally on their Methane Watch platform. They also focus on super emitters and provide data to energy companies, the public sector, and many more. “Companies want to understand their emissions in order to abide/əˈbaɪd/ by regulations on mitigation and methane levels,” says Antoine Rostand, founder and president of Kayross. The company will also work with the International Energy Forum, the world’s largest energy organisation, to develop a measurement methodology for methane that would allow the energy sector to track methane hotspots more accurately and set better mitigation goals as part of their plans to meet the Paris Agreement goals.

Improving satellite observations and reducing uncertainty will help push methane mitigation, which is still in its early days. “ We still have to filter the data a lot – we can only say something about methane emissions if we don’t have interference from clouds. But with plans for new satellites and other smaller ones planned for higher resolution, we will see that in time these instruments will improve their measurements,” says Dr. Aben.

Quantifying methane emissions remains a challenge

Despite observations, 2020’s higher concentrations of methane remain contentious. “We don’t really know the explanation,” says Dr. Frederic Chevallier, a scientist at the Climate and Environmental Sciences Laboratory in Gif-sur-Yvette, France, who says it’s hard to attribute the increase in concentrations to a single factor. How natural sources of methane react to climate change also requires more research to see if changes in rainfall and temperature could trigger higher releases of methane. “Some studies show that with temperature increases, wetlands release more methane,” says Dr. Aben.

Looking a bit further back in time, though, it does not seem that natural sources of methane have emitted much more above the 2000-2006 average, says the Global Carbon Project. On the other hand, emissions from agriculture, boosted by increased red meat consumption, rose by about 12 per cent in 2017, while fossil fuels’ contribution of methane increased by 17 per cent.

Reducing methane emissions in oil and gas is, at least for now, more straightforward than convincing people to start eating less meat. The extractive industry has a range of new technologies to replace old infrastructure, reduce leaks and recover methane, so they need data to know where they need to take action. Production facilities can use satellite observations to spot and address leaks they might be unaware of, which in the end saves them money. “But they are still reluctant/rɪˈlʌktənt/ to take significant action until regulation on methane becomes clearer,” explains Antoine Rostand at Kayross. When it comes to livestock though, things are more complex – mitigation strategies look at changing the diet of ruminants and improving how agro-industrial waste is handled. Some solutions include anaerobic digestion to capture methane from manure or feeding seaweed to cattle/ˈkætl/, which researchers found to reduce by 82 percent of the methane they produce.

Measuring methane remains critical for pushing change across methane-rich industries, especially as 40 per cent of emissions could be mitigated at no extra cost, according to estimates from the International Energy Agency. The latest initiative from the United Nations and the EU Commission is an International Methane Emissions Observatory that aims to improve methane monitoring by creating a more complete picture of emissions – combining company reporting, satellite data, and scientific research. “People realise that they can do something with these measurements,” says Dr. Aben. “It’s slowly starting, and it will take a while, but it is clear things will pick up.”

guilty: tội lỗi

rubbish: rác rưởi

dumps:bãi rác

FOOTPRINT:

garbage: rác

fines: tiền phạt

straightforward: thẳng thắn

permanent: dài hạn

commercial: thương mại

globalization: toàn cầu hóa

engine: động cơ

diverse: phong phú (đa dạng)

deserve: xứng đáng

estate: điền trang

disruption: gián đoạn

archive: lưu trữ

approval: sự chấp thuận

obsession: ám ảnh

handy: tiện dụng

ally: đồng minh

compose: soạn, biên soạn

decomposing: phân hủy

flood: lũ lụt

paddy: thóc

ruminant: nhai lại

burping: ợ hơi

leak: rò rỉ

thaw: tan băng

permafrost: băng vĩnh cửu

potent: mạnh mẽ

intense: dữ dội

intensive: chuyên sâu

concentration: sự tập trung

satellite: vệ tinh

culprit: thủ phạm

distinguish: phân biệt

anthropocentric

urgency: khẩn cấp

slash: gạch chéo

combustion: sự đốt cháy

refine: lọc

momentum: quán tính

momentary: tạm thời

boost: tăng cường

principally: về cơ bản

via: thông qua

coal: than đá

elusive: khó nắm bắt

accurate: chính xác

sampling: lấy mẫu( sampling)

blend: trộn

variation: biến thể

finer: min hơn

coverage: phủ sóng

collaborate: hợp tác

reluctant: lưỡng lữ

cattle: gia xúc

manure: phân

abide:chịu đựng

Despite our obsession with carbon dioxide, methane could be a handier/ˈhændi/handy ally/ˈælaɪ/ to fight climate change

What do a rice field, a cow, a bog, and a coal mine have in common? Well, there might be more than one answer, but one thing is certain: all of them are “gassy”. They all release methane, a gas not as famous as carbon dioxide, yet infamous for its capacity to trap heat. And as its emissions are on the rise, the world is paying more attention to it. Scientists and governments see in methane a way to achieve faster results on climate mitigation. But to tackle methane means knowing exactly how much of it gets into the atmosphere and who’s to blame.

Methane comes from quite a few natural and human-related sources. About a third of its global emissions originate in wetlands, where massive amounts of organic matter produce methane when decomposing/ˌdiːkəmˈpəʊz/. Agriculture is the biggest contributor of human-induced methane, bringing in more than a quarter of anthropogenic emissions, primarily from livestock and crops grown in flooded/flʌd/ paddies/ˈpædi/paddy. Methane is a by-product of manure/məˈnjʊə(r)/ pits and ruminants’/ˈruːmɪnənt/ burping/bɜːp/burp, while in fields, such as rice, bacteria that decompose underwater create methane. Another quarter of the worldwide methane emissions comes from the oil and gas industry, which causes frequent gas leaks/liːk/ and releases methane. Other sources include biomass burning and thawing/θɔː/thaw permafrost/ˈpɜːməfrɒst/.

Khí mê-tan đến từ khá nhiều nguồn tự nhiên và liên quan đến con người. Khoảng một phần ba lượng khí thải toàn cầu của nó bắt nguồn từ các vùng đất ngập nước, nơi có một lượng lớn chất hữu cơ tạo ra khí mê-tan khi phân hủy. Nông nghiệp là ngành đóng góp lớn nhất vào lượng khí mê-tan do con người tạo ra, mang lại hơn một phần tư lượng khí thải do con người tạo ra, chủ yếu từ vật nuôi và cây trồng trên những cánh đồng ngập nước. Khí mê-tan là sản phẩm phụ của hố phân và động vật nhai lại ợ, trong khi ở ruộng, chẳng hạn như lúa, vi khuẩn phân hủy dưới nước tạo ra khí mê-tan. Một phần tư lượng khí thải mê-tan khác trên toàn thế giới đến từ ngành công nghiệp dầu khí, là nguyên nhân thường xuyên làm rò rỉ khí và giải phóng khí mê-tan. Các nguồn khác bao gồm đốt sinh khối và làm tan băng vĩnh cửu.

But what makes methane the second largest contributor to climate change is its power to heat the atmosphere – being about 20 times as potent/ˈpəʊtnt/ per unit as carbon dioxide. This means that releasing 1kg of methane is like emitting 84kg of carbon dioxide. And as global methane emissions are rapidly increasing, we should expect more intense/ɪnˈtens/ warming.

Nhưng điều khiến khí mê-tan trở thành nguyên nhân lớn thứ hai gây ra biến đổi khí hậu là khả năng đốt nóng bầu khí quyển của nó - mạnh gấp 20 lần trên một đơn vị so với carbon dioxide. Điều này có nghĩa là giải phóng 1kg khí metan giống như thải ra 84kg khí cacbonic. Và khi lượng khí thải mêtan trên toàn cầu đang gia tăng nhanh chóng, chúng ta nên mong đợi sự ấm lên dữ dội hơn.

In 2020, methane reached its highest concentrations/ˌkɒnsnˈtreɪʃn/ since satellite/ˈsætəlaɪt/ records began in 2003, according to preliminary data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). The Global Carbon Project indicates a 9 per cent increase in 2017 compared to 2000-2006 and points to agriculture and waste management as two likely drivers of the rise. “Over the past decade, people realised methane was going up really fast – and this is very problematic,” says Dr. Drew Shindell, a climate scientist at Duke University and lead author of the UN’s 2021 Global Methane Report.

Theo dữ liệu sơ bộ của Cơ quan Biến đổi Khí hậu Copernicus (C3S), vào năm 2020, mêtan đạt nồng độ cao nhất kể từ khi ghi nhận vệ tinh bắt đầu vào năm 2003. Dự án Các-bon Toàn cầu cho thấy mức tăng 9% trong năm 2017 so với năm 2000-2006 và chỉ ra rằng nông nghiệp và quản lý chất thải là hai động lực có khả năng dẫn đến sự gia tăng này. Tiến sĩ Drew Shindell, nhà khoa học khí hậu tại Đại học Duke và là tác giả chính của Báo cáo Mêtan toàn cầu năm 2021 của Liên hợp quốc cho biết: “Trong thập kỷ qua, mọi người nhận ra khí mê-tan đang tăng rất nhanh - và điều này rất có vấn đề.

But the culprits/ˈkʌlprɪt/ are still under debate. “Surely, there is a strong human influence in this growth,” says Dr. Ilse Aben, a senior scientist at the SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research and co-principal investigator for the TROPOMI instrument, which makes observations of methane onboard the Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite. “But distinguishing/dɪˈstɪŋɡwɪʃ/ natural from anthropogenic emissions is always complicated.”

While carbon dioxide remains in the air for 300 years, making it a matter of urgency/ˈɜːdʒənsi/ to reduce its emissions, methane stays there only a little over a decade. So slashing /slæʃ/methane emissions could provide quick benefits for climate mitigation. “What we found is that controlling methane is attractive and beneficial,” says Dr. Shindell about the UN report. “For example, if action to reduce methane is taken this year, we would see the concentrations changing already in the year after.” And as methane contributes to pollution – when it mixes with combustion/kəmˈbʌstʃən/ exhausts in the lower atmosphere, it reacts to create ozone which harms our respiratory/rəˈspɪrətri/ system – this reduction could bring immediate health advantages for people.

Refined /rɪˈfaɪn/observations bring the goal closer

Các quan sát tinh tế đưa mục tiêu đến gần hơn

Momentum/məˈmentəm/ for methane mitigation is growing. The European Union’s strategy on methane wants to boost/buːst/ ambition on reducing the emissions of the EU’s dominant non-CO2 greenhouse gas by 35-37 per cent until 2030 (compared to 2005 levels). To do so, it seeks to improve monitoring and reporting of methane emissions principally/ˈprɪnsəpli/ via/ˈvaɪə/ its Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS). Earlier this year, the US State Department also announced it would invest $35 million into REMEDY, a programme that will develop technologies to reduce methane emissions in the oil, gas, and coal/kəʊl/ industries. Globally, 45 countries producing about three-quarters of the world’s methane emissions are part of the Global Methane Initiative, which also focuses on methane mitigation in these industries.

But to reduce methane at the source requires precise monitoring. SRON uses many measurements in-situ across the world, where people take samples of air for analysis explains Dr. Aben. “That network of about 80 stations is quite good for following how methane is roughly changing globally. But it’s not enough to give us information where the sources of methane are.”

Nhưng để giảm khí mêtan tại nguồn cần có sự giám sát chính xác. SRON sử dụng nhiều phép đo tại chỗ trên khắp thế giới, nơi mọi người lấy mẫu không khí để phân tích, Tiến sĩ Aben giải thích. “Mạng lưới khoảng 80 trạm đó khá tốt để theo dõi sự thay đổi của khí mê-tan trên toàn cầu. Nhưng nó không đủ để cung cấp cho chúng tôi thông tin về nguồn khí mê-tan ở đâu. "

Unlike carbon dioxide, methane emissions are more elusive/ɪˈluːsɪv/, explains Dr. Sergio Noce, a researcher at the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change and contributor to the Global Carbon Project. “The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change tells us that uncertainty about CO2 emissions is lower than that of methane, probably because we know more about where CO2 is produced, and the observation network is much more developed. For methane, there is no globally accurate /ˈækjərət/data on production activities, and sampling is not equally distributed […]. We know a lot about some countries and very little or nothing about others.”

“You really need global coverage, and that’s where satellite observations come in,” says Dr. Aben. “Measurements are challenging – once emitted, methane blends/blend/ into the air and travels. So, in a location, you only see an average methane concentration, but the methane you measure might also come from elsewhere. We look at variations/ˌveəriˈeɪʃn/ of these concentrations across the world and try to pinpoint and estimate the emissions.” But the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) can provide a much finer view of emissions, collecting data off small areas of 5 by 7.5km and providing as much as 40 million observations daily. “For the first time, we have full global coverage and high-resolution observations,” says Dr. Aben.

Possibly the most important data needed for mitigation is knowing who the biggest emitters of methane, or super-emitters, are. As natural sources also put significant amounts of methane in the atmosphere, telling what is human-induced and what is natural is still difficult. “In some cases, you might have oil and gas facilities close to wetlands, so it is complicated to tell exactly how much methane is coming from where,” Dr. Aben explains. So determining the super emitters helps.

TROPOMI looks exactly for those super-emitters – point sources such as coal mines or leaks from oil and gas extraction. “We try to focus on the ones that really pop out and analyse that in more detail. We go for the low-hanging fruit,” says Dr. Aben. “We collaborate /kəˈlæbəreɪt/with other partners with smaller satellites who can measure methane at very fine scales.” After TROPOMI detects emissions at global levels, it provides the locations that stand out, and smaller satellites can zoom in on smaller areas to tell which infrastructure is responsible.

TROPOMI tìm kiếm chính xác những nguồn siêu phát thải đó - những nguồn điểm chẳng hạn như mỏ than hoặc rò rỉ từ khai thác dầu khí. “Chúng tôi cố gắng tập trung vào những thứ thực sự nổi bật và phân tích chi tiết hơn. Tiến sĩ Aben nói, chúng tôi đi tìm những kết quả thấp. “Chúng tôi hợp tác với các đối tác khác với các vệ tinh nhỏ hơn có thể đo khí mê-tan ở quy mô rất nhỏ”. Sau khi TROPOMI phát hiện khí thải ở cấp độ toàn cầu, nó cung cấp các vị trí nổi bật và các vệ tinh nhỏ hơn có thể phóng to các khu vực nhỏ hơn để cho biết cơ sở hạ tầng nào chịu trách nhiệm.

Kayross, a European technology start-up, uses data from Copernicus Sentinel-5P, as well as in-situ data and artificial intelligence to monitor methane globally on their Methane Watch platform. They also focus on super emitters and provide data to energy companies, the public sector, and many more. “Companies want to understand their emissions in order to abide/əˈbaɪd/ by regulations on mitigation and methane levels,” says Antoine Rostand, founder and president of Kayross. The company will also work with the International Energy Forum, the world’s largest energy organisation, to develop a measurement methodology for methane that would allow the energy sector to track methane hotspots more accurately and set better mitigation goals as part of their plans to meet the Paris Agreement goals.

Improving satellite observations and reducing uncertainty will help push methane mitigation, which is still in its early days. “ We still have to filter the data a lot – we can only say something about methane emissions if we don’t have interference from clouds. But with plans for new satellites and other smaller ones planned for higher resolution, we will see that in time these instruments will improve their measurements,” says Dr. Aben.

Cải thiện các quan sát vệ tinh và giảm độ không chắc chắn sẽ giúp thúc đẩy giảm thiểu khí mê-tan, vẫn còn trong những ngày đầu. “Chúng tôi vẫn phải lọc dữ liệu rất nhiều - chúng tôi chỉ có thể nói điều gì đó về sự phát thải khí mê-tan nếu chúng tôi không có sự can thiệp của các đám mây. Nhưng với kế hoạch cho các vệ tinh mới và các vệ tinh nhỏ hơn khác được lên kế hoạch cho độ phân giải cao hơn, chúng ta sẽ thấy rằng trong thời gian các thiết bị này sẽ cải thiện các phép đo của chúng, ”Tiến sĩ Aben nói.

Quantifying methane emissions remains a challenge

Định lượng khí thải mêtan vẫn là một thách thức

Despite observations, 2020’s higher concentrations of methane remain contentious. “We don’t really know the explanation,” says Dr. Frederic Chevallier, a scientist at the Climate and Environmental Sciences Laboratory in Gif-sur-Yvette, France, who says it’s hard to attribute the increase in concentrations to a single factor. How natural sources of methane react to climate change also requires more research to see if changes in rainfall and temperature could trigger higher releases of methane. “Some studies show that with temperature increases, wetlands release more methane,” says Dr. Aben.

Looking a bit further back in time, though, it does not seem that natural sources of methane have emitted much more above the 2000-2006 average, says the Global Carbon Project. On the other hand, emissions from agriculture, boosted by increased red meat consumption, rose by about 12 per cent in 2017, while fossil fuels’ contribution of methane increased by 17 per cent.

Reducing methane emissions in oil and gas is, at least for now, more straightforward than convincing people to start eating less meat. The extractive industry has a range of new technologies to replace old infrastructure, reduce leaks and recover methane, so they need data to know where they need to take action. Production facilities can use satellite observations to spot and address leaks they might be unaware of, which in the end saves them money. “But they are still reluctant/rɪˈlʌktənt/ to take significant action until regulation on methane becomes clearer,” explains Antoine Rostand at Kayross. When it comes to livestock though, things are more complex – mitigation strategies look at changing the diet of ruminants and improving how agro-industrial waste is handled. Some solutions include anaerobic digestion to capture methane from manure or feeding seaweed to cattle/ˈkætl/, which researchers found to reduce by 82 percent of the methane they produce.

Measuring methane remains critical for pushing change across methane-rich industries, especially as 40 per cent of emissions could be mitigated at no extra cost, according to estimates from the International Energy Agency. The latest initiative from the United Nations and the EU Commission is an International Methane Emissions Observatory that aims to improve methane monitoring by creating a more complete picture of emissions – combining company reporting, satellite data, and scientific research. “People realise that they can do something with these measurements,” says Dr. Aben. “It’s slowly starting, and it will take a while, but it is clear things will pick up.”

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét